All Possible Fates

The universe is expanding, but my apartment

is not. This is balance I tell myself,

tripping over trikes, toy blocks,

the way a housecat can convince itself a mattress

is wilderness, its very own Savannah,

or how no one in the neighborhood can afford

the neighborhood, though we ghost

past townhouses, pretending they are ours.

In the end, isn’t it in our nature to disperse?

To pull away? When my daughter begs to play

hide-and-seek, I try my best not to find her

immediately, though there are only so many places

to hide. Then one day, sick of ducking

behind sofa cushions, or under the desk, she slips

into the bathroom, snaps down the lock.

Three years old and well out of reach.

Before I knew I too could disappear, I would leap

off balconies, bunk beds and swings, bike

to the brink of each dead-end street.

I write this beside a man weeping into the Arts

& Leisure section of the Times. His lips

are quivering, face wet, yet what can I do but look

away? I look away, but he’s in this now,

fixed inside, like how my daughter was a door

I threatened and pleaded with, until she felt

like having pancakes, and turned the knob. I admit

all fault, to all possible fates. Are we bound

to be an airport where everyone leaves?

![]()

The Man on Fire

(Kaufman Studios Fair–Astoria, NY)

The man on fire is trained not to burn

but to look like he is burning.

Behind him, a woman cascades

off a crane, and at noon, a squad-car

will slam through a barn,

but the man on fire is trained not to burn.

He wears dark clothes, gloves, and a ski-mask.

He places a utility grill lighter to his wrist.

The man on fire becomes the man

on fire as it leaps up his elbow,

his torso, his back. A show-dog, it obeys

him, hurdles and begs. Rolls

and plays dead. Past the cones,

people snap photos of the man on fire.

An artificial snow-maker blows

artificial snow. But the man knows

his gig is short-lived. Soon, even his salves

and fire-resistant fabrics will give,

for while the man on fire is trained not

to burn, his training is no match

for what writhes upon him, this rising

towards ash, a heat-cloak roped

over countless centuries, cities and bodies,

and so the man must signal for his team

to step in before flames recall

what they are and become him.

![]()

The Grounds

Step into this

and reach nowhere

forever: just acres

of grass and absence

and sky, here

you’ll learn to live

with yourself

swallow your echo

bury your goals

surely you can stay

become part

of the grounds

an occasional yellow sign

alerting visitors

of your crossing.

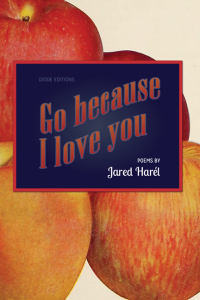

Jared Harél has been awarded the ‘Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize’ from American Poetry Review, as well as the ‘William Matthews Poetry Prize’ from Asheville Poetry Review. Additionally, his poems have appeared in such journals as the Bennington Review, Massachusetts Review, The Southern Review, and Tin House. Harél teaches writing at Nassau Community College, plays drums, and lives in Queens, NY with his wife and two kids.