Assembling Words and Pictures from My Life in Doha

Mise en Scéne: My Arrival in Qatar

On August 3, 2009, my flight landed in Doha, Qatar, a tiny country in the Middle East. As we descended, I peered out the window in an attempt to see the country I was about to call my new home. A mix of clashing emotions rushed through my head, but after over 24 hours spent waiting in airports or on flights, I remained in a state of numb calm. Although I had done a fair amount of traveling prior to this move, I had never lived outside the United States and I didn’t know what life changes awaited me. When the flight landed it was nearly 9 pm. My wife and I debarked the 737 and were instantly whisked to the main terminal to collect our luggage and obtain our temporary residence visas.

From this point, everything was a blur and I barely had time to process all that was going on around me. After leaving the passport control area we headed to the final security check point. We merged into a crowd of people attempting to form some semblance of a line to pass through the luggage scanners. The State of Qatar enforces strict policies that prevent firearms, drugs, alcohol, pork, and pornography into the country. I had a few photography books and movies that might have been questionable, and the thought of unpacking my duct-taped Rubbermaid bins full of personal items in an unorganized crowd of people and in front of guards made me nervous.

Finally, we exited the terminal with a colleague who arrived to pick us up. As soon as we walked outside the terminal door, I was smacked with a wave of hot, moist air that I had previously only experienced in a Finnish style sauna in my home state of Minnesota. That was the moment when reality set in, my exhaustion gave way, and my awareness kicked into hyper-drive. Swarms of Indian and Arabic men surrounded me, shouting and carrying homemade luggage tied with rope. They frantically waved their arms in a gestural language that was alien to me. It was now approaching midnight, and the temperature outside still remained 39 Celsius (about 102 Fahrenheit) with about 80% humidity.

Since it was so late, I naïvely assumed the drive from the airport across the city to our new residence would be fairly simple and quiet. The airport area was fairly calm, but as we approached the center of town, the streets filled with honking cars. They swerved wildly around cars parked on the sides of the streets and darted through roundabouts in a chaotic game of chicken. As we moved through the city we saw people playing in the park with children and having late-night picnics. Immediately, I noticed Qatari men dressed in white robes (called dishdasha or thobe) and red-checkered head dressing (ghutras) that cascaded down their backs like small capes. Muslim women were wearing various styles of abaya, a long black tunic, some were plain and some were lavishly adorned. Some women’s faces were fully covered (niqab), some women covered their hair (hijab), and some wore no headscarf at all. I noticed other women without abayas who were dressed in western style clothing, but they were still wearing scarves; some scarves were wrapped tightly, while others were loosely draped. I also noticed a mix of nationalities, from Indian, Nepalese, and Sri Lankan, to Lebanese, British, Turkish, and Filipino. I had been on the streets of Qatar for less than 15 minutes, and my mind was almost overwhelmed with observations and questions.

Developing a Process: A Visual Audit of “Place”

Over the past several years, I have moved my practice of image-making and graphic design away from my studio and into the surrounding landscape. Although the work I create often comes from sitting with my laptop, printer, and scanner, the ideas, aesthetic, and designs are born from daily observations, encounters, and interactions. After receiving a BFA in visual art and design in 1996, I freelanced for several design and branding agencies in Minneapolis and Portland. At that time much of the client work focused on brand rejuvenation. This meant a team of designers, writers, and other creative thinkers would conduct a creative audit of a company. As a junior designer, my job was to sift through printed marketing materials, identity standards manuals, and advertising, looking for visual consistencies in order to find the company’s personality. Based on that research, I would develop new visual ideas, images, photographic styles, colors, typography, and graphical elements to support the brand and establish new visual systems.

I have been away from branding and corporate marketing for a few years. However, many of the research methods and creative processes I developed during that time period still apply to my work today. Instead of sifting through stacks of marketing materials at a table, I pick up my camera and sketchbook and conduct visual audits by drifting through urban city streets and uncharted territories. My shift from working solely in my studio to working in the external world was influenced by my graduate thesis. At that time, I was introduced to Guy Debord and The Situationists, I read Charles Baudelaire’s notions of the flaneur and I was influenced by a number of photographers such as Steven Shore and Walker Evans, as well as past and present documentary filmmakers Dziga Vertov and Werner Herzog.

Recently, I have been able to travel to many countries in the Middle East and beyond. During my travels I documented my understanding of the world around me using photography, videography, and text. As a graphic designer, I can’t help noticing street signs, typography, colors, and architecture, and how elements juxtapose in a landscape. Everything I see influences my thinking and helps me create new ideas. I don’t take photographs with the intent of creating a great work of art. Photography for me is a form of ethnography that allows me to create a visual study of a place. This process allows me to access my own personal catalog of images to group together into different narratives, or to use as a reference for future projects.

Visual Syntax & Semantics: Translating My Life in Doha

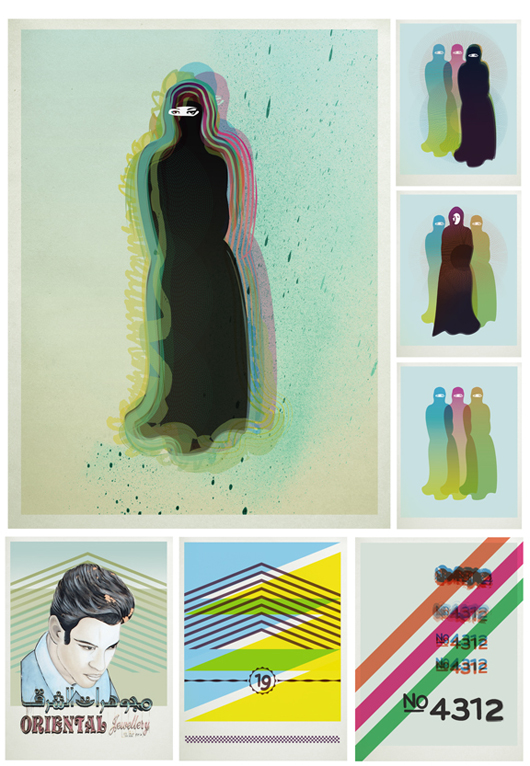

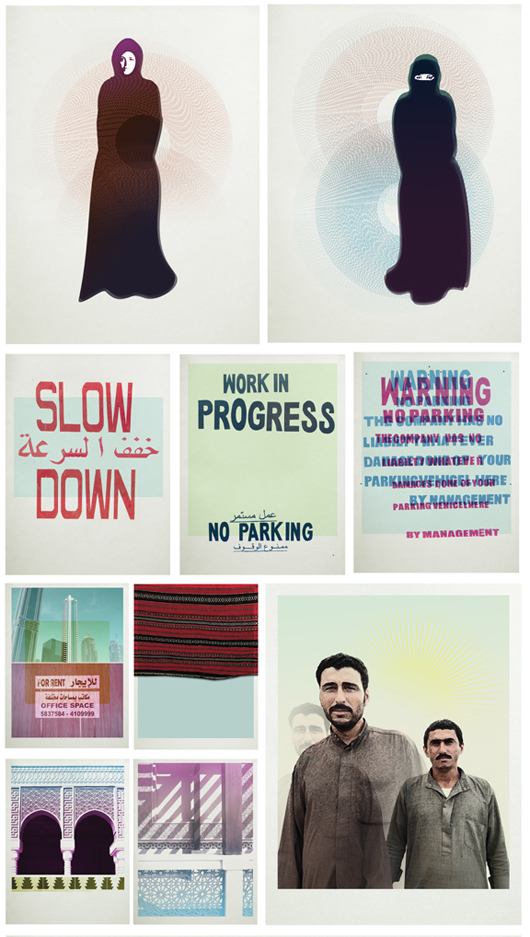

Living in Doha has influenced not only my design, but also how I view life, politics, religion, and our current global culture. At first, I was overloaded by visual information: written languages, collisions of patterns, unfamiliar fashion sensibilities, and cultural artifacts. But after being in Qatar for a year and a half I have grown accustomed to my new landscape. My recent project, “Narratives from an American in Sheikdom,” developed as a reaction to my new surroundings and has enabled me to translate my day-to-day observations and my continuous sense of wonderment into a visual experience.

I began looking through the four hundred-plus photographs I took over the past year from this region. I became fascinated with graphical elements, such as the colored stripes and numbers on the sides of construction trucks, text and illustrations on signs, and other interesting graphical shapes. I was also drawn to the sandy landscape and how everything seems to be covered in a thin layer of yellow dust, a yellow that contrasts with the turquoise sea. I came across images of the orange, pink, and purple hues of sunsets reflecting in the futuristic glass high rises, as well as images of old Persian textiles with rich, slightly faded colors. All of these visual items obliquely told a narrative of place without telling one particular story.

Admittedly, I was a bit overwhelmed and did not know where to start. Based on these images and other day-to-day observations, I randomly selected about 200 photographs and began conducting my own visual audit, which included digitally redrawing images and patterns, replicating graphical shapes, building color palettes, hand-drawing typographic treatments, and rendering digital illustrations. My goal was to create a library of graphical materials that I could utilize like an alphabet to construct a new visual syntax. I envisioned a wall of various-sized prints displayed next to each other like a giant puzzle that appears to be in a state of chaos, yet forms a cohesive narrative of life in Doha as you weave through the individual moments.

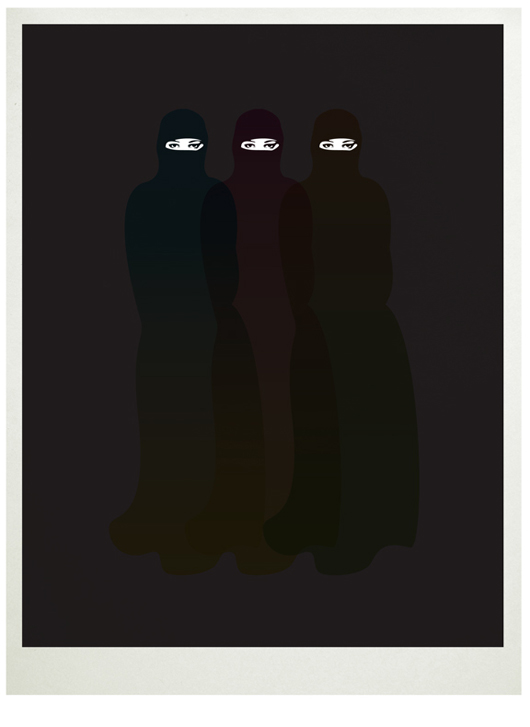

Although I explored a variety of visual content within this project, the digital drawings of the covered women seemed to be a recurring theme. As a Western male, perhaps the most distinct aspect of adapting to culture in the Middle East is to be around large numbers of women wearing full-length, all-black abayas with hijabs and many with full-face coverings. These iconic images of women from Middle Eastern countries seemed to be etched into my mind from the time I arrived. Likewise, certain cultural conventions make it difficult for men and women to interact in public, especially a non-Muslim, non-Qatari man and a Qatari woman. This public scenario contrasts with my experiences with my female students as a professor at VCUQatar. Due to our dynamic classroom environments, I interact with the female students continuously and I have privileged insight into their personalities, families, and aspirations.

These contrasting experiences fueled my creative desire to visually explore the image of a covered woman in the Gulf region. Images of women in abayas are often used in politically motivated campaigns and perpetuate stereotypes that all Muslim women are alike because of the way they dress. I wanted to unveil a different perspective and show that these women have strong individual personalities and aspirations. At the same time, the graphic designer in me wanted to create something that almost resembled a brand or a graffiti stencil, something that seemed familiar yet unique.

The flat illustrative style of the covered women emerged from a graphical style I had used to create the library of images, as well as a need to address a particular local issue. Many women in this region prefer not to be photographed, and if they allow you to photograph them, they often do not want that photographic image to be made public. I looked at the women I had photographed, as well as other online images, and began to digitally sketch shapes that mimicked the flowing black abayas. The eyes and face of the women were made by tracing facial features from different photographs and different people and then combining the results. I focused on the eyes and wanted them to gaze outward to the onlooker, yet remain slightly abstract and without too much detail. Many covered women in this region use exaggerated eyeliner and mascara, and I wanted that aspect to come through graphically as well.

Using the drawings of the women in abayas, I overlaid colors, patterns, textures and graphical elements from my library of visual elements to create complex collages. In some instances the overlaid abaya images create a sense of translucency that seems to subtly hint at body shapes underneath. The elements have become a cohesive system embedding cultural meaning through references of covering and uncovering, revealing and concealing while creating the sense of curiosity, but from a safe distance. Splashes of bright colors appear as if hinting at a hidden world we are not privy to. The black colors used are not a true black, but made of differing percentages of cyan, yellow and magenta. This gave me the ability to control the levels of black. Some are cool; some are warm and subtly play with variations of printing black on black.

The images shown here were created during the fall of 2010 and were displayed in a Faculty Exhibition at Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar. However, much of the work displayed is still in processes and has yet to reach a final form. I view this work as realized sketches that are completed but awaiting the next transition. The images found here are digital files of the Giclee prints produced for the show. The individual images range in size but collectively filled a space approximately three feet wide by ten feet tall. I plan to keep documenting my experience while living in Qatar and adding to my visual library of materials.

Michael Hersrud is a multidisciplinary designer currently working as an assistant professor for Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar. His teaching focuses on time-based and interactive media relative to graphic design. His current research examines the visual language of ‘place’ through an exploration of visual narrative using digital printmaking, typography, photography, web, documentary filmmaking, and motion media. Previously to working in Qatar, he taught interdisciplinary design at Michigan State University. He graduated with an MFA in Graphic Design from RISD in 2006 and conducted Post-Baccalaureate work at the University of Oregon in 2003. He received a BFA in 1996 from Minnesota State University, Moorhead. In addition to graphic design, he has studied letterpress & serigraph printmaking, analog photography, book arts and digital media, as well as engaging in collaborative work with the Multi-media and Electronic Music Experiments program at Brown University. His current work can be found at www.surfacearea.org and his research on time-based media can be found at www.non-linear.org.

|