Home Sweet Home

Woman Mourning Son

—Najaf, Iraq

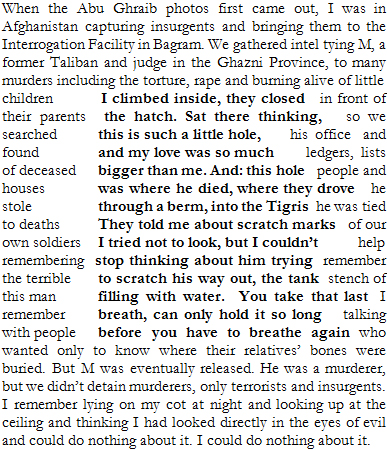

I pull up the blinds, they screech in retreat,

mad grackles beaking for space on the lawn.

I flip open the news and she flutters out,

trailing the blot of her shadow. I yawn,

her mouth yawns and yawns. Like wings, her chador

unfurls over a bare, bleached street. She looks

almost like she’s flying, one leg cut off

by the photo. The shape of her shadow’s

an F-16, the flat plane of her hand

the jet nose, the other hand a missile

tucked so gently beneath the wing. And now

the blot of that shadow’s a flailing bat,

a ragged flag—this black-clad woman’s hands

open and skyward, as if she wants to vault

the blot of this shadow. From above, it looks

just like whirling, a waltz with no one

but chadors and shadows. Now she’s lost

her face in the ink. The road is a white

sheet. Somewhere someone’s hands danced

over a keyboard to deliver the ordnance.

War Stories

The fitful sleep of steak and silver. We

man the monitors of dreaming, on this outpost

of fatherhood. The battlements of silence.

A friend opens a bottle of red. We’ve lived

in this dome so long it seems like freedom.

We know the crackle of distant gunfire

heightened by stereo, the plith of dust,

each stray bullet pirouetting in slo-mo.

Our fathers and brothers wear the flak jacket

of medal and shrapnel. We don the softness

of palms, the odor of diaper wipes. Somewhere

outside, someone’s brother’s buried

a box he won’t tell us where. Inside the box

is. We gird the landscape in the soundtrack

of earbuds, but inside the box is a baby

radio hissing. Inside is the rattle unjawed.

In the rings of our suburbs, outside the zone

of ground zeroes. The baby is stirring, not

crying. Inside the well of our glasses,

the smutch of discernable breathing.

Ass

There are two kinds of wild ass,

the entry begins, in The Children’s

Encyclopedia. A favorite cuss

in Arabic: jahhash. Speaking this tongue

is a house without a number,

inheriting a key to the door

that exists only in the I remember

of elders. Cross-references help

traveling from entry to entry.

In what country, upon crossing

the threshold of a home, would I

remove my shoes, remnant of roads?

What to carry, what should I bear

as gift to the other? Jahhash, my father

said, laughing at the donkey ears

he’d sprouted around a fool’s face.

They were born with everything

we associate with civilization

in the Fertile Crescent. Braying

means “foolish speech.” Illustrations

show you what other books tell you.

Full color photographs and maps.

The Arab-American writer chooses

donkey instead of jackass. It seemed

almost burnished, almost too noble

a translation. The key in donkey,

the Don Quixote. In the Israeli novel

The Smile of the Lamb, a dead ass rots,

once caught in what journalists want

to call “the crossfire,” in the heart

of an occupied town, everyone

walks past, pretends it does not exist,

refusing to move it, lingering

despite the stink, despite maggots,

as if there were nothing festering

at the center of everything. See also

(in the neural wormhole of mind)

Dostoyevsky’s horse, in Karamazov’s

telling, whipped about the eyes—

Ivan’s proof of the distance of God.

Ear, lip, arm, leg—parts of the I

my daughter spelled first. Find the keyword.

The ideal poem, he thought, would slide

like the teeth of gears ground down.

The point: to strip the abandoned car

of all causality. Like one who awoke

to morning, after a long war,

only birds and crickets left to sing.

A language that meant exactly

what crickets mean, rubbing forelegs.

When they’d invaded the city,

commandos first seized the archives

of maps and stories. In State of Siege,

Darwish proposed the ass for the new flag,

half-comedy and half-homage.

It looks like a massacred salad, tabbouli.

Asses need little water, saith the book,

can survive eating spiky grass.

I lean and loaf. I look, don’t look

up. So many bitter herbs. So much lack

to grievance. So many wounds to curse,

jawbone weapons to bless. Some stubborn,

others wisely cautious. Google ass

and find yourself in a forest of humans

doing things to each other we don’t need

to see to believe. So much can be hidden

before us, when everything seems

at our fingertips. Dear beast of burden.

Philip Metres is the author and translator of a number of books and chapbooks, including Sand Opera (forthcoming 2015), I Burned at the Feast: Selected Poems of Arseny Tarkovsky (forthcoming 2015), Compleat Catalogue of Comedic Novelties: Poetic Texts of Lev Rubinstein (Ugly Duckling Presse forthcoming 2014), A Concordance of Leaves (Diode 2013), abu ghraib arias (Flying Guillotine 2011), To See the Earth (Cleveland State 2008), and Behind the Lines: War Resistance Poetry on the American Homefront since 1941 (University of Iowa 2007). His work has appeared in Best American Poetry, numerous journals and anthologies, and has garnered two NEA fellowships, the Thomas J. Watson Fellowship, five Ohio Arts Council Grants, the Beatrice Hawley Award (for the forthcoming Sand Opera), the Arab American Book Award, the Cleveland Arts Prize, the Anne Halley Prize, and a Russian Institute of Translation grant. He is a 2014 Creative Workforce Fellow. The Creative Workforce Fellowship is a program of the Community Partnership for Arts and Culture, supported by the residents of Cuyahoga County through a public grant from Cuyahoga Arts & Culture.He is professor of English at John Carroll University in Cleveland. See http://www.philipmetres.com.

|